Exercise and Heart Health

Regular exercise promotes physical, mental, and social aspects of health. When performed at mild intensity, there is a positive correlation between physical activity and cardiovascular fitness.1 However, as workout intensity increases, so does the heart’s job of supplying oxygen-rich blood to the body’s cells. The cardiovascular system undergoes several physiological changes to optimize this oxygen delivery process in response to training. The term “athlete’s heart” describes these collective changes.1 This exercise-induced, cardiac remodeling closely resembles the changes that occur in response to cardiac pathologies.1 Correctly identifying and managing athlete’s heart cases is key for athletes’ safety and minimizing risks of sudden cardiac death. This condition is up to 4 times more common in athletes than non-athletes of the same age.2

Athlete’s Heart: How Does It Work?

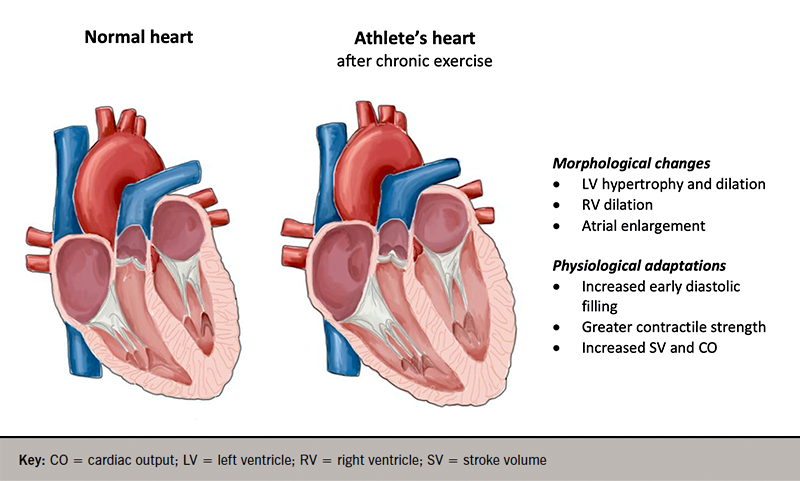

The release of growth factors and neurotransmitters facilitate the exercise-induced changes that ultimately lead to athlete’s heart.3 Insulin growth factor 1 (1GF1) is a hormone mainly produced in the liver, that initiates the observed cardiac growth.3 Norepinephrine also helps increase the cardiac output seen in athlete’s heart via regulating the contractile strength of heart cells.4 These physiological mechanisms are independent from the pathological mechanisms in heart diseases that show similar hypertrophic (tissue enlargement) states. In pathological states, pressure-related mechanical stress releases a different pair of hormonal stimuli not found in athlete’s heart cases.4 Figure 1 below visually demonstrates the physiological changes associated with athlete’s heart.

Figure from: Goh, F. Q. (2021). Can too much exercise be dangerous: what can we learn from the athlete’s heart?. The British Journal of Cardiology, 28(3), 30.

Observed Changes From Athlete’s Heart

All changes that occur in athlete’s heart are a calculated response to a specific stimulus. The type of stimulus involved, and the characteristics of the athlete can dictate how cardiac remodeling manifests. Since most sports consist of separate strength and endurance components, this is an easy way to distinguish between stimuli.1

Strength refers to the intensity of static muscle contractions.1 Endurance is the percentage of maximum aerobic power used during dynamic movements.1 Both static and dynamic activities induce increased oxygen demand for heart cells. Nonetheless, the specific types of changes differ depending on which type of stress the exercise emphasizes. Fundamentally static exercises, like weightlifting, increase blood pressure and heart rate. This usually leads to increased mass and thickness of the heart’s left ventricular wall.6 Running, a form of dynamic exercise, instead demands the maintenance of oxygen delivery via increased heart rate, stroke volume, and systolic blood pressure. Structurally, this appears as a dilation in the chamber size of the heart’s left and right ventricles.6

Individual traits also impact athlete’s heart adaptations. For example, females usually have smaller left ventricular, end-diastolic dimensions than their male counter parts.6 Furthermore, black athletes have considerably greater levels of thickening in their left ventricles compared to white athletes.6 The heart’s ability to maintain normal contractile function rather than decline ultimately distinguishes these changes from those in pathological conditions.5

How Can We Respond to This?

The development of athlete’s heart does not require formal medical interventions. Nonetheless, all athletic settings should apply diagnostic and preventative measures. This is key to eliminate the possibility of cardiomyopathies (underlying heart conditions) and reduce one’s susceptibility to sudden cardiac death.

Sports organizations in certain countries have found electrocardiographic screening fairly useful for identifying heart abnormalities. For example, as of 2006, the implementation of this standard in Italy led to a 90% decrease in sudden cardiac death for young athletes.1 Despite these promising results, the strategy is not universally effective. The United States and Israel did not witness similar reduction in sudden cardiac death cases. Since most athletes with the condition pass these screening tests, the tests are not reliable predictors of athletic health.

Until more reliable solutions are available, high quality clinical histories and physical examinations help rule out other diseases and ensure athlete’s health. Athlete’s heart adaptations are reversible by nature. Thus, athletes should seize training for up to three months to confirm that the changes are physiological, not pathological. It is often unideal for an athlete to stop training for an extended period of time. Nonetheless, this information is important. Health professionals should encourage athletes to make informed decisions about verifying health status.

Want to Learn More?

Interested in learning more about sudden cardiac arrest and other heart conditions prevalent in sport? Watch the video linked here: https://youtu.be/OUINXimUp40?si=VjUPf7EVcnFQYOCS.

References

1https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40279-018-0985-2 2https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8882986/ 3https://www.nature.com/articles/nrd2359 4https://journals.physiology.org/doi/full/10.1152/physiol.00043.2010 5https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/42/13/1231/5983842 6https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/echo.15066?saml_referrer

About the Author

Daniel is a second-year master’s student completing his thesis at McMaster in the kinesiology department.