A study of remote islands show debris and plastic waste alter sand temperatures. This can dramatically affect animal and environmental health.

Henderson Island, a once uninhabited paradise in the Pacific Ocean, is a monument to humanity’s destructive, disposable culture.

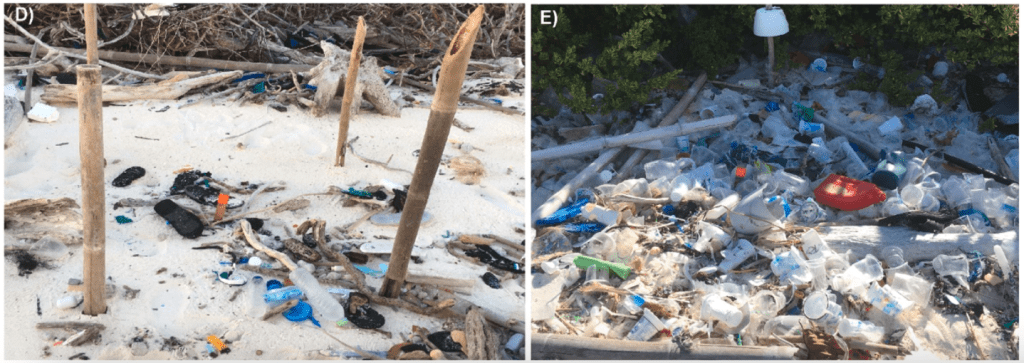

A study found that 18 tonnes of plastic had accumulated along a 2.5 km patch of the sandy beach, amounting to several thousand pieces across decades.¹ Until recently, the origin of this plastic remained unknown. The Island lies in the world’s third-largest marine protected area, where commercial fishing and mining are illegal. Yet, debris is carried ashore by the South Pacific Gyre, a giant current that moves anti-clockwise to East Beach.

Most of the plastic is believed to be from South America and passing ships. This waste consists of netting, shoelaces, fishing devices, razors, bottle caps and even laundry baskets. Ingestion of these plastics by animals can cause organ failure or bioaccumulation in the tissue. Animals can also suffer from starvation because these plastics can stimulate a feeling of fullness.

Recently, research found that single-use items can impact sand temperatures. These temperatures are important for the survival of heat sensitive beach dwellers.

Marine eco-toxicologist Jennifer Lavers, from Australia’s University of Tasmania, investigated beach temperature measurements at Henderson Island and Cocos Island.² To track plastic debris and sand temperatures, the team designed a network of square-foot plots between the two islands where plastic debris was located. The team placed temperature sensors at 2 and 12 inches below the sand to measure variability with depth. A control quadrant with zero debris could not be found because of the widespread debris along shores. Thus, the team settled on patches with the least debris.

Figure 1. Low vs. High density quadrants used for temperature measurement.

The team collected data for a three-month period on hourly and daily bases. In the shallow sensors, temperatures reached a peak of 2.5°C hotter between the low and high-volume plastic sites. In contrast, the daily minimums dropped around 1°C more for high volume versus low volume sites. Temperature differences in deeper senses showed more stability, with the effect disappearing completely with higher plastic layer thickness. This indicated that temperature changes are not because of thermal conductivity, but rather through infrared radiation and reduced convection. Plastic debris buried at 10 cm of depth accounts for 68-93% of beach debris, shielding deeper layers from infrared transfer.

The team also investigated potential reasons for this circadian cycle change and posed different reasons for temperature reasons. During the daytime, the plastic possibly acts as an insulator to trap heat and moisture like a greenhouse. Alternatively, the nighttime cooling effect is more challenging to explain. Possibly, plastics in the sand allow pathways for water and air to dissipate heat more quickly without direct sun exposure.

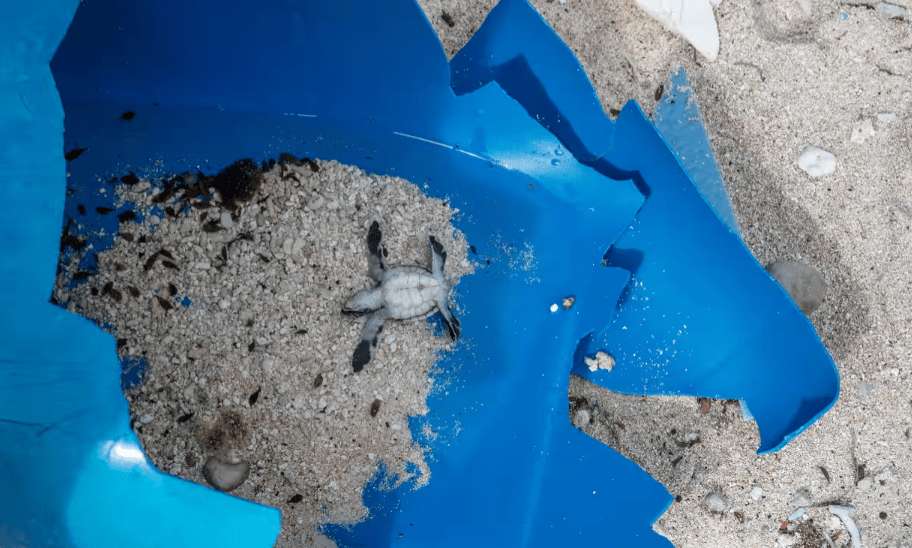

Although the temperature variations seem minimal, a mere one- or two-degree difference can significantly impact coastal animal life. Tropical temperatures are usually very stable, so equatorial animals have adapted to live in very narrow niches. Plastic accumulation is likely to influence the abundance of crab species and diversity found across these beaches. For cold-blooded species like sea turtles, thermal properties are incredibly important to daily function. Sea turtles bury their eggs in the sand on these beaches. Nest temperatures directly relate to sex ratios of baby turtles. Warmer nests can lead to higher feminization rates and impacts fitness and success. Larger hatchlings usually come from cooler nests. Similarly, shore and seabirds that rely on these beaches for nesting can be affected. Plastic can be stored in the birds’ nesting materials and can impact the egg and chicks development.

Image capturing the treat of plastic waste to Henderson Island wildlife. Photo retrieved from Reference 1. Credits to Iain McGregor/The Guardian.

Temperature changes can also impact the microscopic environment of these communities, too. Bacteria and smaller invertebrates are highly temperature insensitive, so this can cause extinctions and thriving of different species. Plastic-driven temperature increases can also increase spread of diseases like avian malaria, with negative changes impacting the entire food chain. Leaching of chemicals in plastics is also still generally not a well studied process. These chemicals can be dangerous for humans, animals and vegetation across the world. This is along with the growing popularity of plastic breakdown into microplastics that are a significant health concern.

These changes in soil biota can have a destabilizing effect on ecosystems, so addressing this problem is an increasing concern. Some experts claim that it is too late to clean up all the accumulated plastic waste. Instead, focus should be on mitigating other threats and buffering current populations from receiving significant effect by these changes.

These plastic-driven temperature changes are not isolated to these locations and will have significant implications on global environmental health. The foundation of the problem is deeply rooted in global, single-use plastic consumption. These changes are important wake-up calls to change global supply chains focused on single-use products. Consumers must recognize that plastic shouldn’t be cheap commodities quickly thrown out, and focus on shifting to a circular economy.

The findings of this research has been published in the Journal of Green Chemistry:

Lavers, J. L.; Rivers-Auty, J.; Bond, A. L. Plastic Debris Increases Circadian Temperature Extremes in Beach Sediments. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 416, 126140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126140

References

²Lavers, J. L.; Rivers-Auty, J.; Bond, A. L. Plastic Debris Increases Circadian Temperature Extremes in Beach Sediments. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 416, 126140.

About the Author

MUSCS

The McMaster Undergraduate Society for Chemical Sciences (MUSCS) is a student-run organization dedicated to enhancing the undergraduate experience for all McMaster University Chemistry & Chemical Biology Students. You can check out their Instagram page here.